Globally, religious persecution is Christian persecution

If there were a Nobel Prize for enduring misery, Nabil Soliman would be an awfully compelling candidate.

Two years ago, the 54-year-old Egyptian Christian was a security guard in his small Upper Egyptian village of Nazlet El Badraman, where his family had lived for generations. Though hardly rich, he and his wife Sabah, along with their six children and five grandchildren, were comfortable and proud of Nabil for being the lone Christian in town to hold such a position of trust.

Then, the sky fell in.

In November 2013, Islamic radicals in his village went on a violent rampage, angry over the removal of Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi as the country’s president. Christians, who represent roughly 10 percent of Egypt’s population, made convenient targets.

Soliman’s was among the first homes to be torched. Rather than restraining the mob, town police instead arrested Soliman, and, as they hauled him away to the station house, invited bystanders to beat him.

He and his family were forced to flee the village or be killed. Soliman lost his job, his pension, and his home. His family survives today in a stifling Cairo flat, living on a share of the meager income two of his sons generate selling second-hand clothes in the streets. He can’t afford the rent, or even to buy the medicines he needs to stave off his hepatitis C, a deadly disease brutally common in Egypt.

Understandably, Soliman is full of questions about his fate and his future. But none of them is “why.”

“This is all because we’re Christians,” he said in an interview this summer. “There is no other reason.”

Such stories and much worse are depressingly easy to collect, in Egypt, across the Middle East, and elsewhere around the world. Religious persecution is increasingly Christian persecution, here and globally. Pope Francis said in July 2014 that “there are more martyrs in the Church today than in the first centuries,” and empirical evidence bears him out.

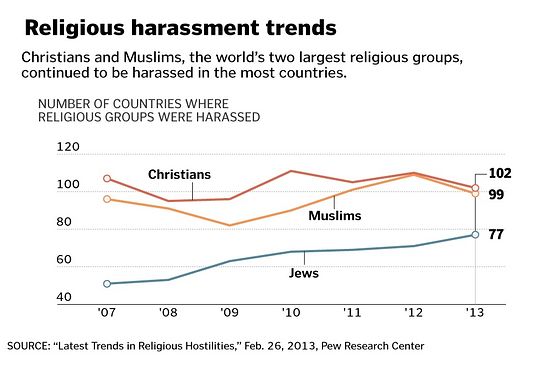

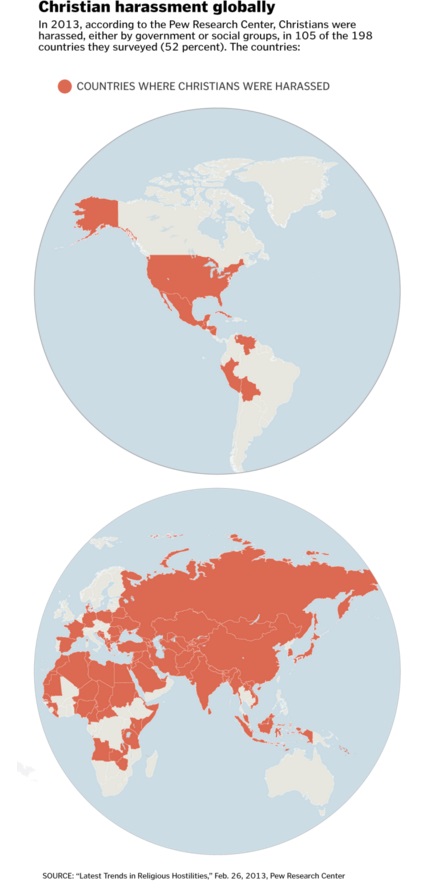

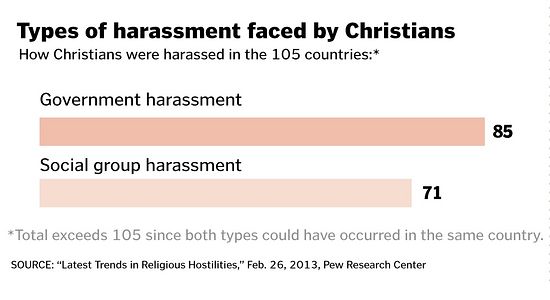

In 2013, Christians were harassed either by the government or social groups in 102 of 198 countries included in a Pew Research Center study, the highest tally for any religious group. An earlier study by other researchers reported a 309 percent jump in attacks on Christians in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

A diverse set of motives drives the persecution. In much of the Middle East and parts of Africa, it’s Islamic radicalism; in India, it’s Hindu fundamentalism; in China and North Korea, it’s police states protecting their hegemony, and in Latin America, it’s often vested interests threatened by Christians standing up for peace and justice. The Globe, in a series that launches today, will report back from all those fronts in this unholy war.

In Egypt, long the mostly-peaceful home to one of the largest and most ancient Christian communities in the region, the root cause lies at the bloody intersection of radical Islamism and radicalized politics, where the mob sets the tone. Victims are everywhere you look.

There’s Nadi Mohani Makar, 59, who was a prosperous merchant in a mid-sized Egyptian town called Dalga when a mob burst into his home in 2014, shot his wife in the leg, set the house ablaze, and dragged him off for a beating. He was held by local police for 15 days, and then informed that he was no longer welcome in town.

Makar has never received compensation for the $260,000 of merchandise he says he lost, and no one has been charged for the shooting of his wife.

Also from Dalga is Saqer Iskander Toos, 35, whose father was killed around the same time. After waiting ten days for a death certificate so the family could bury him, Toos was finally able to organize a funeral – only to watch as the same radicals stormed the cemetery, dug up his father’s corpse, and paraded it through the streets.

When Toos and his brother took video images of the macabre scene to the police, they were told that for their own safety they needed to go into hiding. They live hand to mouth today in Cairo and are still desperately pursuing justice, playing the video on cheap cell phones to anyone who will watch.

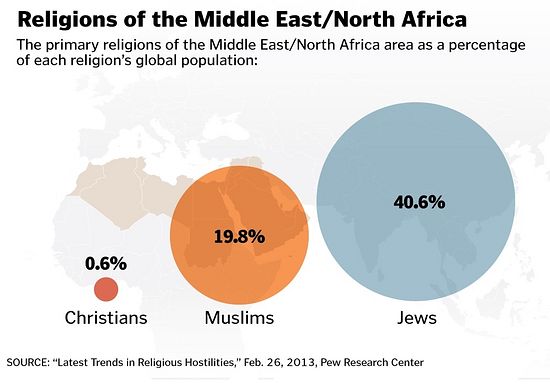

These experiences capture the realities facing many Christians in the Middle East today, where they form the region’s most embattled and, all too often, defenseless minority.

Public attention typically concentrates on Iraq and Syria, where a self-proclaimed “caliphate” led by the Islamic State (ISIS) is engaging in what a spokesperson for the local Catholic community termed in September 2014 a “slow-motion genocide.”

In Iran, despite the moderate profile of a government under Hassan Rouhani that came to power in 2013, Christian pastors face death sentences under a new criminal charge of “spreading corruption on earth.” In Israel, which boasts of being the region’s lone democracy, Arab Christians complain of second-class status and harassment by security forces. Even in Lebanon, where Christians form a robust 40 percent of the population, Archbishop Georges Bou-Jaoude of Tripoli says that young Christians today “live in anxiety and fear.”

Many observers believe today’s wave of anti-Christian prejudice could be a prelude to gradual regional extinction.

“We may be witnessing the final act of Christianity’s long decline in the very place where it was born,” says George J. Marlin, author of the 2015 book “Christian Persecutions in the Middle East.”

That is, while anti-Christian violence has become a global commonplace, nowhere are the threats as overt or as widespread than in the land where Jesus lived and preached.

A unique risk

Christians are, of course, hardly the only community facing savagery and oppression.

Though precise numbers are difficult to come by, it’s widely believed that the leading victims of Islamic radicalism are their fellow Muslims. In some cases, they’re members of a Muslim minority group such as the Shi’ites, Alawites, or Ahmadiyya; in others, they’re moderate members of the Sunni majority who have run afoul of fundamentalist currents.

In October 2014, the United Nations released a report detailing almost 10,000 civilian deaths at the hands of ISIS in the first eight months of the year, the clear majority of whom were Muslims. Those casualties included three Sunni women in Mosul executed for refusing to provide medical care to Islamic State fighters, a female doctor killed for refusing to wear a veil while treating patients, and several Sunni men beheaded for refusing to swear allegiance to the group.

Other religious groups also find themselves in the firing line. In Iraq, Christians often stand alongside Yazidis, practitioners of an ancient syncretistic faith akin to Zoroastrianism, in fleeing Islamic State onslaughts. In other nations, Jews, Bahais, Zoroastrians, Druze, and other communities are experiencing similar trauma.

It’s also true that just because a victim is Christian doesn’t necessarily mean the motives for the persecution are exclusively, or even primarily, religious. There are all manner of ethnic and nationalistic forces potentially at work.

Still, Christians in the Middle East are often uniquely at risk, in part because of their perceived identification with the West.

Mina Thabet, a researcher with the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, a Cairo-based nongovernment human rights organization, said it’s an old story.

“From the era of the Islamic conquest, Christians in the Middle East have been seen as a foreign presence, as the ‘other,’ even though their roots here are actually much deeper,” he said.

“Whenever Muslims get mad at the West, it’s harder to take it out directly on the Americans or the EU,” Thabet said. “It’s much easier to march to the Christian church down the street and torch it.”

Egypt as a test case

Egypt is perhaps the best test case for Christian prospects in the Middle East, a country where one might have thought Christians would find at least a basic quantum of stability and security.

Egypt has by far the Middle East’s largest Christian footprint. There are more than 8 million Christians here, and it is a staple of local rhetoric that they’re the “original Egyptians,” heirs to the country’s ancient heritage and language.

Egypt is also among the Middle Eastern nations most sensitive to Western opinion. Since a 1979 peace deal with Israel, it’s been the second largest recipient of American foreign aid, and the Obama administration recently lifted a hold on the transfer of military equipment that had been imposed after the army seized power.

None of that, however, inspires much confidence in Wadie Ramses, a 63-year-old Egyptian doctor and Coptic Christian.

During the 92 days Ramses was held captive in the Egyptian desert in the summer of 2014, blindfolded and handcuffed at all times, the most terrifying moments came when he could overhear his radical Muslim kidnappers debating whether to behead him or keep him alive to collect a ransom.

“We can’t cut off his head,” Ramses remembers one of the kidnappers saying. “There are many more Christians. We need money, and the families will only pay if they know we’ll give their relatives back.”

Another kidnapper pressed to execute Ramses to make a loud statement about how Christians aren’t welcome. But eventually the profit motive prevailed.

Ramses was held for three agonizing months. He suffered two broken ribs and a fractured arm, inflicted during beatings during which his captors insulted him as an “atheist” and a “pig.”

Periodically, Ramses said he would be put in a car and driven for hours to another location to make phone calls to his son who was trying to negotiate his freedom. During those periods, he said, his captors would read aloud verses from the Koran and whip him for refusing to believe in their precepts.

“They’d ask me how, as an educated man, I could believe that God had a son,” he said. “Then they’d ask me if I believe in the Koran, and when I said I didn’t because that would make me a Muslim, they’d use a plastic whip.”

The final ransom, he said, came to roughly $200,000. That wasn’t his only loss, since death threats forced him to abandon his clinic and school. Ramses also says that local police were complicit in his suffering.

“I know some of the men who beat me were members of the security forces,” he said. “If they had wanted to rescue me, they had multiple chances to do so.”

Assurances of protection also ring hollow for many Zabbaleen — Cairo’s legendary “garbage people” – an overwhelmingly Christian underclass of 50,000 to 70,000 people who collect and recycle the city’s gargantuan mounds of refuse, using pick-up trucks and donkey-drawn carts.

The Zabbaleen face various forms of discrimination, some based on class and socio-economic standing, but much of it specifically religious. They say it comes not just from agitated radicals, but also from police and security forces aligned with the radicals’ views.

In a typical incident in late July, a 33-year-old Zabbaleen assistant pharmacist named Ayman Samwel was awakened at 3 a.m. when police burst into his home.

When Samwel’s wife cried out in protest, he told the Globe, the police slapped her into submission. They proceeded to drag him through the streets to a local station house, beating him along the way with fists and batons and shouting abuse – including, he said, a colloquial insult in Arabic that translates roughly as, “[Expletive] your Christianity!”

Samwel displayed his wounds to Globe reporters, including lacerations to his fingers, arms, back, and feet – partly sustained, he said, when he was forced to stand naked and blindfolded in the station for more than four hours as police continued to beat and stomp him at will. They also ripped a medal of a Catholic saint from around his neck.

His arrest was linked to an incident one month before, when a Cairo police officer was called to the neighborhood to settle a quarrel between two families. Witnesses say the quarrel had already been settled, but the officer nonetheless fired his weapon several times in an attempt to disperse a small crowd, with one of those bullets killing a pregnant Christian woman and mother of two.

The Rev. Botros Roshdy, a Coptic priest who ministers among the Zabbaleen, minces no words about why he believes such incidents occur: “All this is because we’re Christians,” he said.

Far from better days after the fall of a Muslim Brotherhood government, Botros says that today things are “ten times worse” in Egypt than under former ruler Hosni Mubarak just a few years ago.

“We thought the police would start a new era with the people,” he said, “but it hasn’t happened.”

Ramses agrees. Asked for his forecast about the future for Christians in Egypt, Ramses was blunt: “Very bad,” he said..

The police won’t apprehend those who hurt Christians, he said, judges won’t prosecute their persecutors, schools won’t educate their children, and the government considers Christians second-class citizens.

Sporting the tattoo of a small black cross on his wrist that Copts wear as a symbol of identity, Ramses says he’s not going anywhere. On the other hand, he says, “I can also understand why Christians would want to get the hell out of here.”

Small reasons for hope

Despite the many frightening incidents and the grim trend of events, those inclined to optimism can find a basis to hope that Christianity stands a fighting chance of surviving and even growing again in the Middle East.

In 2008, for instance, Qatar opened its first new Catholic church since the seventh century Muslim conquest, Our Lady of the Rosary. In June 2014, King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa of Bahrain agreed to donate land for the construction of another Catholic church, to be called “Our Lady of Arabia.”

Counterintuitively, there’s a burgeoning Christian presence today on the Arabian Peninsula. Expansion is coming not among Arab converts, but rather with foreign expatriates increasingly relied on for manual labor and domestic service. Scores of Filipinos, Indians, Sri Lankans, Pakistanis, Koreans, and members of other nationalities are becoming the new working poor in some of the world’s wealthiest societies.

In the Catholic Church alone, the number of believers on the peninsula is estimated at around 2.5 million. Kuwait and Qatar are home to between 350,000 and 400,000 Catholics, Bahrain has about 140,000, and Saudi Arabia itself has 1.5 million.

Some analysts believe that to accommodate those swelling groups of foreigners, wealthier Muslim societies will be forced to make some accommodations on religious freedom.

There are also plenty of moderate Islamic leaders such as Mufti Mohammed Rashid Qabbani, spiritual head of Lebanon’s Sunni community, who have said that they don’t want Christians to leave – in part, he says, because many of the region’s best schools, hospitals, and social service centers would go with them.

When Pope Benedict XVI visited Jordan in 2009, he blessed the cornerstones for two new Catholic churches as well as a new Catholic university operated by the Patriarchate of Jerusalem – all signs of a Christian community determined to hold on. Those projects had the support of Jordan’s King Abdullah II, who himself studied at Georgetown, one of America’s premier Catholic institutions.

In some ways, Jordan illustrates that another path for the Middle East is possible.

Christians are only about 3 percent of the population, but by law they hold almost 10 percent of the seats in the national parliament. Christians also occupy a disproportionate share of senior positions in both the public and private sectors, and Jordanian law recognizes their right to take time off from work for Sunday worship.

For all that, it’s impossible to miss the growing sense of despair that has gripped the Christian community.

“We feel forgotten and isolated,” said Patriarch Louis Sako, Iraq’s Catholic leader, at a conference in Rome in December 2013.

“We sometimes wonder, if they kill us all, what would be the reaction of Christians in the West? Would they do something then?”

Nothing since he spoke that day has made his question sting less.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου